El Fin de un Mundo

“Toda transformación exige como precondición el fin de un mundo: el colapso de una antigua filosofía de vida.” — Carl Jung

“Eres una persona diferente.”

He escuchado esta frase tal vez nueve veces en los últimos tres meses. La mayoría de las veces, se ha sentido como un cumplido. Otras veces, ha sonado a preocupación, condescendencia y decepción. Pero incluso las reacciones que me provocaron punzadas de vergüenza y dudas me recordaron lo que he logrado: he cambiado.

No me refiero a que mi pelo sea más largo y mi piel más bronceada, a que haya adoptado nuevos intereses y abandonado otros, a que viva en un lugar diferente y pase tiempo con personas diferentes, aunque todo esto sea cierto. Cuando digo que he cambiado, quiero decir que poseía un sentido del yo que murió y dio paso a algo nuevo. Estoy hablando de un cambio en el núcleo de quien soy.

Antes, vivía en Nueva York. Estaba a finales de mis veinte y había ascendido desde un puesto de ventas de nivel inicial hasta el equipo directivo de una empresa tecnológica en fase de crecimiento. Tenía un grupo unido de amigos y una serie de novias hermosas e impresionantes. Mis padres estaban juntos. Mis familiares más cercanos estaban vivos. Todo esto hacía que cualquier actitud que no fuera la de una dicha implacable se sintiera vergonzosa.

La visión del mundo que me había llevado hasta allí era dura y rígida. Cuando un profesor de inglés me encargó escribir sobre mi trabajo soñado, describí liderar una toma de control activista de Nike e instalarme como CEO. Cuando un amigo cuestionó si mi estilo de trabajo era sostenible, respondí: “Todo es sostenible”. Cuando un compañero de trabajo rechazó un ascenso para el que no se sentía preparado, me burlé. La receta era máxima inteligencia, ambición y ética de trabajo. La recompensa era dinero, poder y prestigio.

Pero, mientras mi vida sobre el papel prosperaba, mi mente y mi cuerpo se rebelaban. Mi monólogo interior se volvió oscuro. Había vislumbrado los pasillos de prestigiosas instituciones académicas, gubernamentales y corporativas esperando encontrar la buena vida. En cambio, vi cangrejos en un barril, empujándose y agarrándose, desesperados por llegar a la cima. Las intenciones nobles se derrumbaban bajo el peso de la política. Los líderes competentes eran descartados por leales. Los valores y las declaraciones de misión eran herramientas para manipular a los crédulos. Las mentiras eran rutinarias. Oscilaba entre el disgusto por la refriega y la ansiedad paralizante de que perecería dentro de ella.

La constante agitación mental abrumó mi cuerpo. La tensión mantenía mi cuello, espalda y hombros en un tornillo, luego se irradiaba por la parte superior de mi cráneo y hacia mi cara. Mis ojos lagrimeaban. Podía sentir los nervios disparando en mis dientes. Las situaciones estresantes — vuelos, citas, presentaciones — me encontraban paseando frenéticamente o con arcadas secas hasta que no podía respirar. Mi mente corría y mi cuerpo se contraía toda la noche.

Así que no elegí exactamente cambiar — fui forzado. Tal vez esa es la única manera en que sucede. Pero ya fuera por necesidad o por fracaso personal, me encontré ahogándome en ira y miedo. Antes de que pudiera tener lugar cualquier reinvención, tenía que poner mi cabeza justo por encima de la superficie de estas aguas turbulentas.

Estabilidad

“El agua turbia, dejada reposar, se vuelve clara.” — Lao Tzu

Navegar por el cambio requirió relajar mi cuerpo y permitir que mi mente dejara a un lado sus esfuerzos frenéticos y defensivos. Comí saludablemente, hice ejercicio, medité, fui a terapia, despedí a mi terapeuta, encontré un mejor terapeuta. Por primera vez, levanté el pie del acelerador en el trabajo. Seguir triturando era inútil. Era una máquina sobrecalentada — engranajes desgastándose, humo saliendo de su motor.

Los dolores de cabeza y ataques de pánico disminuyeron, y el sueño y la tensión muscular mejoraron. Pero el resultado no fue lo que había esperado. El resultado podría describirse mejor como “meh”. Caminaba pesadamente por las calles de Nueva York cada día, absorbiendo el gris paisaje urbano y pensando para mí mismo: “¿Esto es realmente lo que estoy haciendo con mi vida?”

Afortunadamente, mis esfuerzos por estabilizarme trajeron un beneficio secundario — crearon la convicción de que necesitaba cambiar fundamentalmente. Habiendo hecho lo básico correctamente, habiendo agotado las respuestas fáciles y producido resultados insatisfactorios, los únicos caminos que quedaban eran, por definición, drásticos.

El cambio radical requeriría enfrentarse a dónde me había encontrado en la vida.

Aceptación

“Nada es más deseable que ser liberado de una aflicción, pero nada es más aterrador que ser despojado de una muleta.” — James Baldwin

Era innegable. Mi sentido del yo se había estrellado de frente contra un muro de realidad. Al principio, me enfurecí contra la implicación. Le grité a un terapeuta que sugirió que podría no querer realmente lo que afirmaba querer: — ¿Por qué estás tratando de impedir que me convierta en lo que se supone que debo ser? Pero, con reflexión, la evidencia era difícil de refutar. Cuanto más me acercaba a lo que ostensiblemente quería, más miserable me volvía. Mi cuerpo gritaba que algo estaba mal.

Un examen más profundo de mi psicología — su perfeccionismo neurótico, intensa ansiedad social alrededor de superiores y fantasías recurrentes de escape — reforzó la idea de que no había estado viviendo para mí mismo. Los recuerdos de la infancia insinuaban los orígenes de mi mentalidad implacable — la decepción de mis padres cuando no logré entrar en universidades de la Ivy League, la diatriba de mi padre de que “repudiaría” a asociados insuficientemente dedicados si fueran sus hijos, y cenas familiares pasadas difamando a compañeros de clase perezosos, estúpidos o mal comportados. Había internalizado un juicio severo y lo había ejercido contra todos, incluido yo mismo.

Mi vida, impulsada por la validación externa y la evitación del juicio, se había vuelto intolerablemente precaria. Estaba construyendo un castillo de naipes. Nunca podría crecer lo suficientemente alto, pero cuanto más alto se hacía, más difícil era mantenerlo en pie. Cada día, algo nuevo amenazaba con derribarme — la crítica de un amigo, una reunión combativa, un interés amoroso no comprometido.

Este no podía ser el camino. No quería dejar de lado la ambición y convertirme en un suburbano sedado y sin energía, pero tampoco quería seguir jugando los juegos de estatus que aborrecía. La implicación era aterradora y dolorosa de aceptar — yo no era quien pensaba que era. Quién era yo seguía siendo una pregunta abierta.

Inspiración

“La inspiración existe, pero tiene que encontrarte trabajando.” — Pablo Picasso

Mi búsqueda comenzó revisitando intereses que había descuidado durante mucho tiempo. Tomé una guitarra por primera vez en 16 años y entrené para una carrera por primera vez en 8. Estaba tambaleándome — cumpliendo con todos los estereotipos de la crisis de identidad del hombre urbano. Y, como los torpes progresiones de acordes y los poco impresionantes tiempos de milla atestiguan, estos experimentos no se mantuvieron. Pero construyeron impulso. Y eso era mejor que quedarse quieto.

Mis intentos de cambiar pronto se enfrentaron a una prueba crucial. Recibí una llamada inesperada de mi CEO mientras estaba sentado en el aeropuerto de San Francisco un viernes por la tarde. Nuestro Jefe de Finanzas estaba renunciando y yo debía asumir sus funciones. La noticia desencadenó un sentimiento desconocido — no quería saber nada de esto. Había pasado tanto tiempo diciéndome a mí mismo que mi vida era demasiado buena para cuestionarla, que las oportunidades profesionales que recibía eran demasiado buenas para dejarlas pasar. Pero esta deferencia a racionalizaciones embriagadoras solo me mantenía atrapado.

El lunes por la mañana, entré en la oficina de mi CEO, rechacé el ascenso y presenté mi renuncia.

Me había asustado a mí mismo con mi aparente imprudencia. Pero por el amor de dios al menos había hecho algo diferente. Al menos sentí algo. Y así la acción inspiró acción. En tres meses, dejé mi trabajo, rompí con mi novia, renuncié a mi contrato de alquiler y abordé un vuelo al otro lado del mundo. Los primeros días de mi viaje en Asia no fueron explícitamente sobre encontrar identidad; fueron sobre despertar un gusto por la vida dormido durante mucho tiempo. Fui a surfear y a bucear. Monté motocicletas a través de selvas y arrozales. Tomé hongos, luego me senté junto al océano, viendo cómo montañas y nubes de colores psicodélicos bailaban en el horizonte.

Sintiéndome abierto a la experiencia y más confiado en perseguir cualquier camino que me llamara, comencé a inspirarme en otros. No había apreciado cuánto mis círculos homogéneos en casa habían limitado mi sentido de posibilidad. Conocí a un hombre sueco que se mudó a Laos por amor, una mujer tailandesa que dirigía tours gastronómicos para turistas asiáticos en Italia, un estadounidense construyendo una casa para sí mismo en la jungla, y a innumerables otros simplemente viajando hasta que se acabara el dinero. Admiraba su audacia, su desprecio por las convenciones, su ligereza de ser. En sus vidas, vislumbré fragmentos de un camino que se sentía auténtico para mí.

La inspiración no solo vino de las personas que conocí, ni siquiera de los vivos. Mientras estaba en el extranjero, me sumergí en la literatura clásica. Camus presentó una visión para la felicidad enraizada en abrazar la absurda indiferencia del universo. Thoreau defendía una vida de simplicidad y realización espiritual sobre la búsqueda hueca de riqueza material. Hesse instaba al cultivo de una brújula moral interna, capaz de armonizar los deseos conflictivos del yo. La lectura ofrecía lecciones que parecían llegarme en el momento perfecto de la vida. Me recordaba que, durante siglos, las personas habían luchado con las mismas ansiedades y encontrado un camino.

Después de meses de exploración, me sentía ligero, energizado y optimista. Nuevos conceptos de cómo moverme por el mundo habían comenzado a arraigarse. Pero la inspiración no contaba para nada sin el coraje de actuar.

Coraje

“El hombre no puede descubrir nuevos océanos a menos que tenga el coraje de perder de vista la costa.” — André Gide

Cultivar el coraje no fue tanto un paso dentro de mi viaje como un requisito durante todo el viaje. Al principio, reunir coraje para hacer un cambio fundamental es una paradoja. Salvar tu vida puede parecerse mucho a arruinarla, así que nadie te sacudirá por los hombros y te dirá que cambies. Pero al mismo tiempo, si estás considerando volar tu vida en pedazos, probablemente no estés rebosante de la confianza para tomar la decisión por tu cuenta.

Así que, al principio, fingí. Buscar inspiración ayudó a formar el andamiaje de esta fachada. Ser inspirado es tomar prestado el coraje de otros; el ejemplo se convierte en permiso para actuar. Las emociones intensas — incluso las malsanas — proporcionaron combustible adicional cuando la duda persistía. La impulsividad y el desafío teatral me llevaron a dejar mi trabajo. La ira terminó mi relación, mientras que el resentimiento hacia la conformidad a mi alrededor me llevó al extranjero. Mi objetivo final era actuar desde un lugar de calma convicción, guiado por mi brújula interna, incluso frente al riesgo. Pero por ahora, el coraje prestado y la emoción reprimida eran suficientes.

Con el tiempo, mi convicción interna creció. Me encontraba repitiendo ciertas máximas en mi mente cada vez que el miedo se infiltraba. “Sin puerto seguro” — estaba a la deriva, pero si daba la vuelta me ahogaría. “Siempre sabrás” — la salida fácil me costaría mi autorrespeto. “El coraje de ser odiado” — la desaprobación de aquellos con quienes no me identificaba no solo era inevitable, era una señal de que estaba forjando mi propio camino.

Deliberadamente practiqué el coraje. Sentí miedo, enfrenté el miedo, tomé un riesgo, me di cuenta de que estaba bien, sentí que el mundo se expandía, repetí. Tenía miedo a la soledad, así que viajé solo. Tenía miedo al océano, así que fui a bucear. Tenía miedo a volar, así que salté de un avión. A medida que los sentimientos de miedo — el latido rápido del corazón, el estómago revuelto y el sutil temblor de mis manos — se volvieron familiares, noté un cambio. Estas señales biológicas ya no eran solo advertencias — eran invitaciones. Tal vez estaba a punto de crecer. Tal vez incluso me divertiría un poco.

Desarrollar coraje me dejó más libre que nunca, más capaz de elegir un camino auténtico, sin ataduras por miedo o juicio.

¿Y ahora qué?

“Tu nueva vida te va a costar tu antigua… No importa. Todo lo que vas a perder es lo que fue construido para una persona que ya no eres.” — Brianna Wiest

Entonces, ¿quién soy ahora? Evidentemente, soy un ex trabajador tecnológico de pelo largo que se mudó al extranjero, comenzó a surfear y ahora escribe ensayos pseudo-filosóficos en Substack. El cliché es casi insoportable.

En serio, no lo sé exactamente, pero tampoco creo mucho en el concepto convencional del yo. Para mí está claro que gran parte de mi dolor vino de aferrarme a una imagen rígida de cómo tenía que ser, y cómo el mundo tenía que ser a mi alrededor. No deja mucho espacio para aprender o crecer o interactuar con la realidad.

Porque ya no hay nada que tenga que ser, no hay nada que defender. No tengo que tener miedo al futuro. Otras personas pueden ser amigos potenciales, no amenazas potenciales. Y es más fácil juzgar a otros con menos dureza cuando estoy haciendo lo mismo conmigo mismo.

Todavía soy escéptico del dinero, el poder, el estatus y las instituciones que los confieren; creo que estaba en algo allí. Eso me deja sintiéndome un poco perdido a veces. Necesito ganarme la vida, y no quiero ser un misántropo.

Pero no estoy sin rumbo. Este período de la vida ha cristalizado mis valores — autenticidad, curiosidad, amor — y las prioridades necesarias para mantenerlos — libertad, coraje, salud física y mental. Ahora veo que la ambición y la felicidad no son mutuamente excluyentes. Era una falsa elección que me mantenía estancado, un producto de la miopía profesional y metas que no eran mías.

Así que seguiré persiguiendo el emprendimiento — no para la dominación capitalista, sino para la autodeterminación y la expresión creativa. Aprenderé español y cumpliré mi sueño de vivir en el extranjero. Surfearé. Leeré vorazmente. Escribiré este ensayo con el conocimiento de que puede ser juzgado duramente.

Estoy seguro de que vendrá más cambio. Convertirse en el auténtico yo es una lucha continua. Pero ahora puedo confiar en que, pase lo que pase, tengo una brújula para guiarme. Temo más a la ansiedad complaciente que a lo que el mundo pueda traer.

Así que, como no hay una conclusión clara para mi historia, terminaré con esto. Si estás pasando por una crisis de identidad, estás en el mejor lugar de la vida en el que jamás hayas estado. Durante muchos años, posiblemente toda tu vida, algo estaba mal. Vivías según un código que no era el tuyo. La tensión solo ahora se ha vuelto intolerable, pero ha estado allí todo el tiempo. Ahora, finalmente tienes la oportunidad de arreglarlo. Lo que te espera es una vida auténtica, hecha para ti.

© All rights reserved G.B. Heron

G.B. Heron es un ensayista estadounidense radicado en la Ciudad de México. Escribe sobre lo que da sentido a la vida — la autenticidad, la curiosidad y el amor — y el coraje que requieren. Sus ensayos se publican en gbheronessays.substack.com.

The Ending of a World

“Every transformation demands as its precondition the ending of a world—the collapse of an old philosophy of life.” — Carl Jung

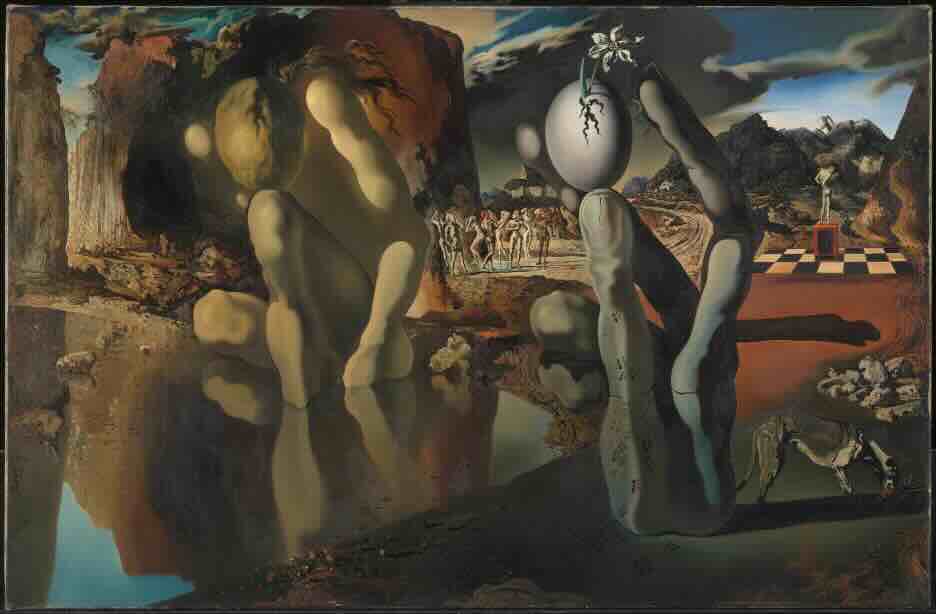

Dalí, Salvador. The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. 1937, Tate Modern, London. Oil on canvas.

“You’re a different person.”

I’ve heard this refrain maybe nine times in the last three months. Most times, it has felt like a compliment. Other times, it has felt like worry, condescension, and disappointment. But even the reactions that gave me pangs of embarrassment and self-doubt reminded me of what I have accomplished: I have changed.

I don’t mean that my hair is longer and my skin tanner, that I have taken up new interests and left others behind, that I live in a different place and spend time with different people, though all these are true. When I say that I have changed, I mean that I possessed a sense of self that died and gave way to something new. I am talking about change at the identity layer of being.

Before, I lived in New York. I was in my late 20s and had worked my way up from an entry-level sales position to the leadership team of a growth-stage tech company. I had a tight-knit group of friends and a series of beautiful and impressive girlfriends. My parents were together. My closest family members were alive. The whole thing made having any attitude other than unrelenting bliss feel shameful.

The worldview that had gotten me here was harsh and rigid. When an English teacher tasked me with writing about my dream job, I described leading an activist takeover of Nike and installing myself as CEO. When a friend questioned whether my working style was sustainable, I replied, “Anything is sustainable.” When a coworker turned down a promotion he didn’t feel ready for, I scoffed. The recipe was maximal intelligence, ambition, and work ethic. The reward was money, power, and prestige.

But, while my life on paper was thriving, my mind and body rebelled. My inner monologue turned dark. I had glimpsed the halls of prestigious academic, governmental, and corporate institutions expecting to find the good life. Instead, I saw crabs in a barrel, jostling and clawing, desperate to reach the top. Noble intentions collapsed under the weight of politics. Competent leaders were discarded for loyalists. Values and mission statements were tools to manipulate the gullible. Lies were routine. I vacillated between disgust at the melee and paralyzing anxiety that I would perish within it.

Constant mental turmoil overwhelmed my body. Tension kept my neck, back, and shoulders in a vice, then radiated over the top of my skull and into my face. My eyes watered. I could feel nerves firing in my teeth. Stressful situations—flights, dates, presentations—found me frantically pacing or dry heaving until I couldn’t breathe. My mind raced and my body twitched all night.

So I didn’t exactly choose to change—I was forced. Maybe that’s the only way it ever happens. But whether out of necessity or personal failure, I found myself drowning in anger and fear. Before any reinvention could take place, I had to get my head just above the surface of these choppy waters.

Stability

“Muddy water, let stand, becomes clear.” — Lao Tzu

Navigating change required relaxing my body and allowing my mind to set aside its frenetic, defensive efforts. I ate healthily, exercised, meditated, went to therapy, fired my therapist, found a better therapist. For the first time, I took my foot off the gas at work. Grinding on was futile. I was an overheating machine—gears stripping, smoke pouring from its motor.

The headaches and panic attacks did subside, and the sleep and muscle tension improved. But the result was not what I had hoped for. The result could best be described as “meh.” I trudged through the streets of New York each day, taking in the gray urban landscape and thinking to myself, “This is really what I’m doing with my life?”

Fortunately, my efforts to stabilize brought an ancillary benefit—they built conviction that I needed to fundamentally change. Having done the basics right, having exhausted the easy answers and produced unsatisfying results, the only paths left were, by definition, drastic.

Radical change would require reckoning with where I had found myself in life.

Acceptance

“Nothing is more desirable than to be released from an affliction, but nothing is more frightening than to be divested of a crutch.” — James Baldwin

It was undeniable. My sense of self had run headlong into a brick wall of life experience. At first, I raged against the implication. I shouted down a therapist who suggested that I might not truly want what I claimed to: “Why are you trying to stop me from becoming what I am supposed to become?” But, with reflection, the evidence was hard to refute. The closer I got to what I ostensibly wanted, the more miserable I became. My body was screaming that something was wrong.

Deeper examination of my psychology—its neurotic perfectionism, intense social anxiety around superiors, and recurring fantasies of escape—reinforced the idea that I had not been living for myself. Childhood memories hinted at the origins of my unforgiving mindset—my parents’ disappointment when I failed to get into Ivy League schools, my father’s rant that he’d “disown” insufficiently dedicated associates if they were his children, and family dinners spent smearing lazy, stupid, or poorly-behaved classmates. I had internalized severe judgment and wielded it against everyone, including myself.

My life, propelled by external validation and avoidance of judgement, had become intolerably precarious. I was constructing a house of cards. It could never grow tall enough, but the taller it got, the harder it became to keep it standing. Every day, something new threatened to topple me—a friend’s critique, a combative meeting, a noncommittal love interest.

This could not be the way. I did not want to set aside ambition and become a listless, sedated suburbanite, but nor did I want to continue playing the status games I abhorred. The implication was frightening and painstaking to accept—I was not who I thought I was. Who I was remained an open question.

Inspiration

“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working.” — Pablo Picasso

My search began by revisiting interests I had long neglected. I picked up a guitar for the first time in 16 years and trained for a road race for the first time in 8. I was flailing—fulfilling every stereotype of the urban male quarter-life crisis. And, as stilted chord progressions and underwhelming mile times will attest, these experiments didn’t stick. But they built momentum. And that was better than standing still.

My attempts to change soon met a pivotal test. I received an unexpected call from my CEO while sitting in the San Francisco airport on a Friday afternoon. Our Head of Finance was resigning and I was to take over his remit. The news triggered an unfamiliar feeling—I wanted no part of this. I had spent so much time telling myself that my life was too good to question, that the professional opportunities I received were too good to pass up. But this deference to heady rationalizations had just kept me trapped. Monday morning, I walked into my CEO’s office, declined the promotion, and put in my notice.

I had frightened myself with my apparent recklessness. But for the love of god at least I had done something different. At least I felt something. And so action inspired action. Within three months, I left my job, broke up with my girlfriend, gave up my lease, and boarded a flight to the other side of the world. The early days of my travel in Asia were not explicitly about finding identity; they were about awakening a long dormant zest for life. I went surfing and scuba diving. I rode motorbikes through jungles and rice paddies. I took mushrooms, then sat by the ocean, watching mountains and technicolor clouds dance on the horizon.

Feeling open to experience and more confident in pursuing whichever paths called me, I began drawing inspiration from others. I had not appreciated how much my homogenous circles at home had limited my sense of possibility. I met a Swedish man who moved to Laos for love, a Thai woman leading food tours for Asian tourists in Italy, an American building a house for himself in the jungle, and countless others simply traveling until the money ran out. I admired their boldness, their disregard for convention, their lightness of being. In their lives, I glimpsed fragments of a path that felt authentic to me.

Inspiration didn’t just come from the people I met, nor even the living. While abroad, I immersed myself in classic literature. Camus presented a vision for happiness rooted in embracing the absurd indifference of the universe. Thoreau championed a life of simplicity and spiritual fulfillment over the hollow pursuit of material wealth. Hesse urged the cultivation of an inner moral compass, one capable of harmonizing the self’s conflicting desires. Reading offered lessons that seemed to reach me at the perfect moment in life. It reminded me that, for centuries, people had wrestled with the same anxieties and found a way.

After months of exploration, I felt light, energized, and optimistic. New concepts of how to move through the world had begun to take hold. But inspiration counted for nothing without the courage to act.

Courage

“Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.” — André Gide

Cultivating courage was not so much a step within my journey as a requirement throughout its entirety. In the beginning, summoning courage to make fundamental change is a Catch-22. Saving your life can look a lot like ruining it, so no one will shake you by the shoulders and tell you to change. But at the same time, if you’re even considering blowing up your life, you’re likely not brimming with the confidence to make the call on your own.

So, at first, I faked it. Seeking inspiration helped form the scaffolding of this facade. To be inspired is to borrow the courage of others; example becomes permission to act. Intense emotions—even unhealthy ones—provided additional fuel when self doubt persisted. Impulsivity and theatrical defiance led me to quit my job. Anger ended my relationship, while resentment of the conformity around me drove me abroad. My ultimate aim was to act from a place of calm conviction, guided by my internal compass, even in the face of risk. But for now, borrowed courage and pent-up emotion would do.

With time, my internal conviction grew. I found myself repeating certain maxims in my mind whenever fear crept in. “No safe harbor”—I was adrift, but if I turned back I would drown. “You’ll always know”—the easy way out would cost me my self respect. “The courage to be disliked”—disapproval from those I didn’t identify with was not just inevitable, it was a sign I was forging my own path.

I deliberately practiced courage. I felt fear, faced fear, took a risk, realized I was okay, felt the world expand, repeated. I was afraid of loneliness, so I traveled alone. I was afraid of the ocean, so I went scuba diving. I was afraid of flying, so I jumped out of a plane. As feelings of fear—the rapid heartbeat, churning stomach, and subtle trembling of my hands—became familiar, I took note of a shift. These biological signals were no longer just warnings—they were invitations. Maybe I was about to grow. Maybe I would even have a little fun.

Developing courage left me freer than ever, more capable of choosing an authentic path, unbound by fear or judgment.

What now?

“Your new life is going to cost you your old one… It doesn’t matter. All you’re going to lose is what was built for a person you no longer are.” — Brianna Wiest

So who am I now? Evidently, I am a long-haired former tech worker who moved abroad, took up surfing, and now writes pseudo-philosophical essays on Substack. The cliché is almost unbearable.

In seriousness, I don’t know exactly, but I also don’t believe much in the conventional concept of the self anymore. It’s clear to me that much of my pain came from clinging to a rigid picture of how I had to be, and how the world had to be around me. Doesn’t leave much room for learning or growth or engaging with reality.

Because there is nothing I have to be anymore, there is nothing to defend. I don’t have to be afraid of the future. Other people can be potential friends, not potential threats. And it’s easier to judge others less harshly when I am doing the same with myself.

I am still skeptical of money, power, status, and the institutions that confer them; I think I was onto something there. That leaves me feeling a little lost sometimes. I need to make a living, and I don’t want to be a misanthrope.

But I am not rudderless. This period of life has crystallized my values—authenticity, curiosity, love—and the priorities needed to uphold them—freedom, courage, physical and mental health. I now see that ambition and happiness are not mutually exclusive. This was a false choice that kept me stuck, a product of careerist myopia and goals that were not my own.

So I will still pursue entrepreneurship—not for capitalist domination, but for self-determination and creative expression. I will learn Spanish and fulfill my dream of living abroad. I will surf. I will read voraciously. I will write this essay with the knowledge that it may be harshly judged.

I am sure more change will come. Becoming one’s authentic self is an ongoing struggle. But I can now trust that, whatever happens, I have a compass to guide me through. I fear indulgent anxiety more than I fear whatever the world will bring.

So, because there’s no clear conclusion to my story, I will end with this. If you are going through an identity crisis, you are at the best place in life that you have ever been. For many years, possibly your whole life, something was wrong. You lived according to a code that was not your own. The tension has only now become intolerable, but it has been there all along. Now, you finally have the opportunity to fix it. What awaits is a life that’s authentic to you.