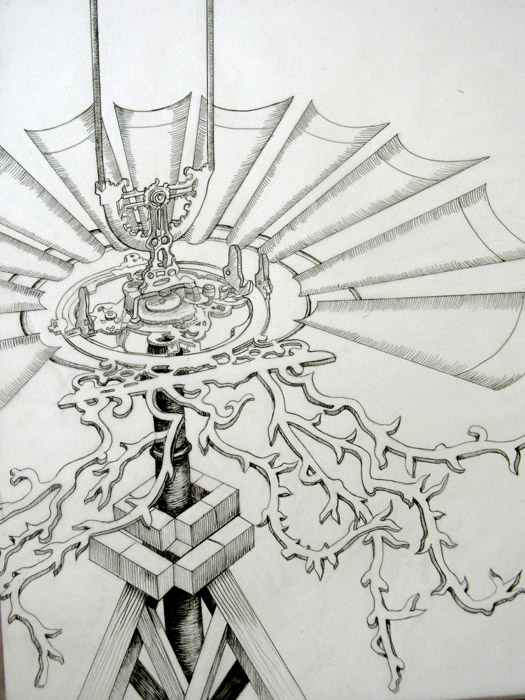

El aparato giraba obedeciendo las leyes inmutables de la sincronía. Cada pieza comunicaba a las otras un movimiento preciso a través del riguroso metal de su estructura. La tensión de un muelle se liberaba con solidez por todo el engranaje hasta desembocar en un elemento que, sin cansarse, oscilaba alrededor de sí mismo, del centro de su centro, para establecer la regulación que rige los asuntos de los hombres.

Las manos del relojero ajustaban el artefacto como una deidad creadora en el momento de dar los últimos toques a la obra que será, por designio, el testimonio del mysterium en todo el futuro por venir. Se trataba de un reloj inglés, una máquina impecable cuyos tornillos y engranajes fabricara en persona el famoso Ramsden, hombre apasionado por la exactitud y la pericia. Pertenecía a un adinerado surtidor de cacao de la Calle de la Concepción. El tic-tac producía un eco que rebotaba en las paredes del cuarto cerrado, iluminado apenas por dos velas mortecinas. Así, mientras el relojero miraba la oscilación inquieta del volante de bronce, los laberintos de su memoria se retorcían de maneras aviesas y conducían a los días en que éste aprendiera la relojería y el arte terrible del relox universal, la técnica mediante la cual se ajusta la sincronía de la máquina con la de los astros del cielo. Su maestro decía: el tiempo y el destino son uno solo.

Para el dominio del arte se requerían años de aprendizaje en la variación de tiempos y estaciones, la observación de las estrellas y la caída de los granos en el reloj de arena. Se debía tener una conciencia serena acerca de la muerte, rectora del movimiento del engrane, además de amplia destreza en la manipulación de los números. Los números eran su vocación primera. Desde pequeño contaba. Números y más números fueron pronunciados por su boca. Nunca supo nadie del origen de ese apego. Contaba todo ante sus ojos: los pájaros en los álamos, los cirrus en el cielo, los balcones de las plazas, las casas de las calles, las calles mismas. Enumeraba los toques de las campanas eclesiales, los pasos que daba alguien de un lugar a otro, las palabras en el sermón de los domingos, las letras de tal o cual libro… Una vez quiso contar las luces del cielo estrellado, pero el sueño lo venció antes de conseguirlo y se sumió en un despeñadero oscuro, donde el alma confundida descubre nuevas preferencias. A partir de entonces, experimentó un singular placer al contar sólo cosas excepcionales como los graznidos de los cuervos, los gorjeos de la lechuza vaticinando la muerte, los gemidos que daban en el orgasmo las criadas al copular en los graneros con los sirvientes, los aullidos penosos de los perros en la intemperie o el doblar de las campanas en fechas fúnebres. Su tutor, José de Zaragoza, se desconcertó al hallarlo contando las hormigas que devoraban el cadáver de un pájaro.

Un día descubrió por accidente su habilidad para hacer cálculos sin recurrir al papel: regresaba a casa de De Zaragoza y luego de haber mirado la numeración de las casas en una avenida pronunció sin querer una cifra. No tardó en percatarse de que aquel número no era otro sino la suma de los que había divisado, hecho que comprobó haciendo la suma en el suelo con un trozo de carbón. Todo aparecía en la mente. Transcurrido el tiempo le era posible, de un único vistazo, saber si las cuentas de la casa eran exactas y varias veces calculaba las más largas en cuestión de segundos. El astrónomo poblano don Miguel Francisco de Ilarregui le pidió computar las epactas del año lunar. Otra ocasión, en una visita con su protector a la biblioteca de Palafox, elevó mentalmente al cuadrado, y luego al cubo, la cantidad de libros de ésta, dejando boquiabiertos a los presentes. Los números eran, pues, la razón de su existencia.

Al partir José de Zaragoza a una larga misión evangelizadora, lo encomendó a Dios y le deseó suerte con el oficio que le enseñara. Podía hacer lo que desease. Él guardó un duelo de tres días. Luego se sintió dueño de sí y decidió probar con las andanzas. Recorrió poblaciones de Cholula, Huejotzingo y el Valle de Texmelucan. Trató con menesterosos y ladrones. Convivió con herejes y estafadores de todas las calañas. Durmió con aventureros y rebeldes que ya hablaban de liberar a la plebe de la corona española. De día trabajó para granjeros y terratenientes y por las noches se refugió en posadas. Cierta ocasión, en la añosa hostería El Fogón, despertó sobresaltado: gotas pegajosas de sudor lavaban su frente. Tenía la urgencia de algo. Un sueño le trajo a la memoria aquel instante del pasado que cambió su vida y le costó el exilio. El día del eclipse. Una larva hiriente empezó a retorcerse en los intersticios de su vientre. Se persignó varias veces como aprendiera de De Zaragoza, pero la Providencia no acudió en su auxilio. Transcurridos varios meses, comprobó que no podía contenerse más. En las posadas frecuentó a las prostitutas que en voz baja le llamaron a sus aposentos: la mayoría de las mujeres eran desdentadas y feas, sólo pocas eran jóvenes como Policarpo. Una de ellas, Crescencia, se decidió a instruirlo en los goces de la carne, mismos que procuraron al principio deleita a Policarpo, y luego un remordimiento debido a las anteriores enseñanzas de su mentor. El jesuita le había previsto de la tentación perjudicial de las mujeres de toda clase. Por las noches Crescencia dormía con Policarpo sin que éste la tocase más. Éste volvía a pensar en su necesidad esencial, imposible de descifrar. Asistió donde había enfermos graves, pero nadie estaba próximo a morir. Acudió a lugares donde el trabajo era peligroso, mas no había accidentes que cobrasen vidas, como tampoco halló víctimas de estocadas o golpes fatales al recorrer caminos frecuentados por salteadores. Nuevamente permanecía despierto durante las noches, hundido en mares de inquietud, mientras la joven prostituta juntaba su cuerpo al suyo, pronunciando en el sueño nombres de amantes anteriores a él. Policarpo dio a la mujer las pocas monedas que le quedaban y le pidió que se marchase para siempre. Dejó pasar algunas semanas hasta que cierto domingo, entrada la tarde y aprovechando el descuido de un pastor, hurtó un cordero tierno. Llevó a la criatura a su posada. Llegada la noche, bajo el manto de la oscuridad cuyos dominios son la mitad del mundo, estranguló mesuradamente al animal para escuchar, con nitidez, los signos de su asfixia y enumerarlos. Apenas se tranquilizó. Al poco tiempo volvió a estrangular, ahora a un perro. Siguieron más ovejas. Cuando no hallaba estos animales debía conformarse con gallinas. A veces se introducía por las noches donde los pesebres y con una soga estrangulaba mulas y yeguas. La gente empezó a alarmarse al descubrir muertas a sus bestias, se organizó en grupos que recorrían con antorchas y lámparas las veredas de noche, precedidos por perros de agudo olfato. Él huía a otros poblados y se internaba en los bosques profundos del Popocatépetl. Cerca de una casucha abandonada encontró un ganso enorme y lo llevó consigo. Al iniciar su ritual de muerte con el ave, el animal aleteó con fuerza y logró liberar momentáneamente el pescuezo, dándole un fuerte picotazo en plena garganta: desde entonces menguó el timbre de su voz. Aquella característica, unida a su palidez y lo perdido de su mirada, terminó por infundirle la apariencia de un autómata parlante.

Sólo después de quince meses De Salazar pudo sentir alivio pleno: paseaba por un riachuelo cuando llegó adonde un campesino se bañaba. Se ocultó entre los arbustos de la hondonada adyacente al río para no ser visto, esperó con frialdad a que el hombre se vistiera. De pronto, a modo de soplo repentino cayó sobre éste y apretó el cuello de la presa. Para entonces sus manos eran ya dos tenazas férreas que estrujaban a conciencia, con dosis controladas de presión, como maquinaria medieval construida para el caso. El campesino, con los ojos descompuestos, jadeó hincado ante su verdugo, quien en voz alta jadeó también, pero con placer, hasta que todo se redujo a un número. Al final, satisfecho, talló en el tronco del árbol más cercano al cadáver la cifra crucial. Era un número bello, pues se trataba de un impar primo.

Después de largos devaneos decidió que regresaría al lugar que lo vio nacer. Llegó al mediodía con un maletín maltrecho donde se hallaban sus escasas pertenencias. Avanzó por esas calles que tantos años dejara de ver, pero que reconocía a pesar de haberse modificado. Policarpo de Salazar y Hurtado estaba ya instruido en las cosas de la vida y contaba con tres ocupaciones: era relojero, calculista y asesino.

The device turned, obeying the immutable laws of synchrony. Every piece communicated a precise movement to every other piece through the rigorous metal of its structure. The tension of a spring was released soundly through every tooth of the gears until flowing into an element that tirelessly oscillated around itself, from the center of its center, to lay down the rules that govern the matters of men.

The clockmaker’s hands adjusted the artefact like a deity at the moment of putting the finishing touches on the creation that would be, by design, the proof of the mysterium for all future to come. It was an English clock, an impeccable instrument whose screws and gears were assembled in person by Ramsden himself, a man impassioned by exactitude and expertise. A belonging of a wealthy cacao merchant from Conception Street. The tick-tock produced an echo that ricocheted off the walls of the locked room, scarcely illuminated by two dying candles. And so, while the clockmaker watched the restless oscillation of the bronze balance wheel, the labyrinths of his memory twisted in malicious ways and led to the days when he would learn clockmaking and the terrible art of the universal klock, the technique with which to adjust the machine’s synchrony to that of the heavenly bodies. His master would say: time and fate are one and the same.

Mastery of this art required years of training in the variation of times and seasons, the observation of stars, and the falling of the grains of sand in the hourglass. Also necessary was a serene consciousness of death, the guiding engine of the cogs’ movement, as well as ample skill in the manipulation of numbers. Numbers were his first vocation. He counted from an early age. Numbers and more numbers were pronounced by his mouth. No one ever discovered the origin of this fondness. He counted everything in his sight: the birds in the poplar trees, the cirrus clouds in the sky, the balconies over the plazas, the houses on the streets, the streets themselves. He enumerated the peals of the church bells, the steps of a passerby from one place to another, the words in the Sunday sermon, the letters of one book or another… Once he wanted to count the lights of the starry sky, but sleep overcame him before he could succeed, and he plunged down a dark precipice where the confounded soul discovers new preferences. From then on, he experienced a singular pleasure only when counting exceptional things, like the caws of the crows, the twitters of an owl foreseeing death, the moans before the orgasms of the maids as they copulated in the granary with the servants, the pitiful howls of the dogs left outside or the tolls of the bells on funeral days. His tutor, José de Zaragoza, was unsettled to find him counting the ants that devoured the cadaver of a bird.

One day, by chance, he discovered his ability to make calculations without using paper: he returned to De Zaragoza’s house and, after having numbered the houses on a certain avenue by sight, he unwittingly pronounced a figure. He took little time to realize that the number was none other than the sum of those he had observed, a fact he confirmed by scratching out the sum on the floor with a piece of coal. All appeared in his mind. In time, he was able to know if the household accounts were exact with a single glance, and often he would calculate even the longest arithmetic in a matter of seconds. Don Miguel Francisco de Ilarregui, the astronomer of Puebla, requested that he compute the epacts of the lunar year. On another occasion, on a visit with his guardian to the Palafox library, he mentally raised the quantity of books on its shelves to the second power and then to the third, leaving all those present open-mouthed. Numbers were the reason of his existence.

When José de Zaragoza departed on a long mission of evangelization, he commended his student to God and wished him luck in the trade for which he was instructed. He could do as he wished. The student proceeded to mourn for three days. After this, he felt himself to be his own master, and he decided to test his fortune elsewhere. He passed through the settlements of Cholula, Huejotzingo, and the Valley of Texmelucan. He did dealings with thieves and paupers. He lived with heretics and swindlers of all stripes. He slept alongside adventurers and rebels who already spoke of freeing the masses from the Spanish crown. By day he worked for farmers and landholders and by night he sought shelter in nearby inns. On one occasion, in the fine old lodging El Fogón, he awoke with a start: sticky drops of sweat wetted his forehead. He felt the urgency of something. A dream brought to his memory that past instant that changed his life and caused his exile. The day of the eclipse. A stinging larva began to wind its way through the interstices of his gut. He crossed himself several times, as he had learned from De Zaragoza, but Providence refused to come to his aid. After several months, he understood that he could no longer contain himself. In the inns, he frequented the prostitutes who softly called him to their quarters: most of the women were toothless and ugly, only a few were young like Policarpo. One of them, Crescencia, took it upon herself to instruct him in the pleasures of the flesh, which at first drew out delight from Policarpo, and then a deep regret due to the prior teachings of his mentor. The Jesuit had warned him of the injurious temptation of women of all classes. In the night, Crescencia slept beside Policarpo, but he touched her no more. He thought again of his essential need, impossible to decipher. He made himself present around the gravely ill, but none was close enough to death. He looked to places where the work was dangerous, but there were no accidents to claim lives, just as there were no victims of knife thrusts or fatal blows to be found when he walked the paths frequented by highwaymen. Once again, he lay awake throughout the night, sunken in seas of unease, while the young prostitute pressed her body against his, pronouncing in her sleep the names of former lovers. Policarpo gave the woman the few coins he had left and requested that she leave forever. He allowed a few weeks to pass until, a certain Sunday, late in the afternoon and taking advantage of a shepherd’s inattention, he snatched up a little lamb. He brought the creature to his inn. When night fell, under the cover of the darkness whose dominions cover half the world, he strangled the animal with measured pressure that he might plainly hear and enumerate the signs of its asfixia. He was scarcely soothed. Not long later, he strangled again, this time a dog. More sheep followed. When no such animals were to be found, he had to settle for hens. Sometimes he found a way into the stables at night and with a rope he strangled mules and mares. The people began to grow alarmed upon discovering their dead beasts, they formed groups that patrolled the paths with torches and lamps at night, preceded by sharp-nosed dogs. He fled to other villages and took refuge in the deep forests of Popocatépetl. Near an abandoned shack, he found a huge goose and carried it with him. As he began his ritual of death with the bird, the animal forcefully flapped its wings and managed to free its neck for a moment, giving him a strong blow with its beak, straight to the throat: from then on, the timbre of his voice was diminished. This characteristic, along with his paleness and the lost look in his eyes, gave him the appearance of a talking automaton.

Only after fifteen months could De Salazar feel complete relief: he was walking along a stream when he reached the spot where a peasant was bathing. He hid himself among the bushes of the hollow adjacent to the river so as not to be seen and waited coldly for the man to dress himself. Suddenly, like an abrupt gust of wind, he fell upon him and tightened his grip around the neck of his prey. By then, his hands were already two iron tongs that squeezed shut with purpose, with controlled doses of pressure, like a medieval mechanism constructed for this very aim. The peasant, with panicked eyes, gasped on his knees before his executioner, who gasped aloud as well, but with pleasure, until all was reduced to a number. In the end, satisfied, on the trunk of the tree nearest the cadaver, he carved the crucial figure. It was a beautiful number, odd and prime.

After long dalliances, he decided to return to the place that saw him born. He arrived at midday with a battered case that contained his scarce belongings. He advanced through streets that he had not seen in many years, but that he recognized in spite of their changes. Policarpo de Salazar y Hurtado was now learned in the matters of life and he boasted three occupations: he was clockmaker, calculist, and murderer.

© All rights reserved Isaí Moreno

© All rights reserved for translation Arthur M. Dixon

Isaí Moreno (Ciudad de México, 1967). Escritor. Autor de las novelas Pisot (Premio Juan Rulfo a Primera Novela 1999), Adicción (2004), además de El suicidio de una mariposa (2012). Con Orange Road obtuvo en 2016 el Premio Nacional de Novela Corta Juan García Ponce. Imparte talleres de novela y es profesor-investigador en la carrera de Creación Literaria de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México. Colabora en revistas literarias, suplementos y blogs culturales como Nexos, Letras Libres, La Tempestad, Lado B, Nagari Magazine, etc. Sus cuentos forman parte de antologías como Así se acaba el mundo (Ediciones SM, 2012), Tierras insólitas (Almadía, 2013) y Sólo cuento (UNAM, 2015). Posee un doctorado en matemáticas por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y en 2010 se licenció por la UNAM en Lengua y Literaturas Hispánicas con la tesis Hacia una estética de la destrucción en la literatura. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte de México.

Isaí Moreno (Ciudad de México, 1967). Escritor. Autor de las novelas Pisot (Premio Juan Rulfo a Primera Novela 1999), Adicción (2004), además de El suicidio de una mariposa (2012). Con Orange Road obtuvo en 2016 el Premio Nacional de Novela Corta Juan García Ponce. Imparte talleres de novela y es profesor-investigador en la carrera de Creación Literaria de la Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México. Colabora en revistas literarias, suplementos y blogs culturales como Nexos, Letras Libres, La Tempestad, Lado B, Nagari Magazine, etc. Sus cuentos forman parte de antologías como Así se acaba el mundo (Ediciones SM, 2012), Tierras insólitas (Almadía, 2013) y Sólo cuento (UNAM, 2015). Posee un doctorado en matemáticas por la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y en 2010 se licenció por la UNAM en Lengua y Literaturas Hispánicas con la tesis Hacia una estética de la destrucción en la literatura. Es miembro del Sistema Nacional de Creadores de Arte de México.

Isaí Moreno (Mexico City, 1967) is the author of the novels Pisot [There Are Not So Many Stars] (Juan Rulfo First Novel Prize, 1999), Adicción [Addiction] (2004), and El suicidio de una mariposa [The Suicide of a Butterfly] (2012). He was awarded the 2016 Juan García Ponce National Short Novel Prize for Orange Road. He leads novel-writing workshops and is a professor and researcher in the Creative Writing program of the Universidad Autónoma de la Ciudad de México. He contributes to literary magazines, supplements, and cultural blogs such as Nexos, Letras Libres, La Tempestad, Lado B, Nagari Magazine, etc. His stories have been included in anthologies such as Así se acaba el mundo [That’s How the World Ends] (Ediciones SM, 2012), Tierras insólitas [Unheard-Of Lands] (Almadía, 2013), and Sólo cuento [I Only Tell the Story] (UNAM, 2015). He holds a doctorate in mathematics from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, and in 2010 he earned a degree from UNAM in Hispanic Language and Literatures with the thesis Hacia una estética de la destrucción en la literatura [Toward an Aesthetics of Destruction in Literature]. He is a member of Mexico’s National System of Creators of Art.

No son tantas las estrellas (edición definitiva de Pisot)

There Are Not So Many Stars (definitive edition of Pisot)

Edición bilingüe

Publicado por katakana editores (2019)